Before Anne Borg was finally diagnosed with breast cancer, she woke up early every week to be first in line by 6 a.m. for a medical consultation at a government-run hospital in Cape Town, South Africa.

Although the hospital wasn’t far, it was a long wait at the overcrowded clinic full of other medically uninsured South Africans.

“I don’t have medical insurance, and so I couldn’t afford everything that was going on. All the tests needed. You can get them quicker if you do it privately,” Borg explained. “At the public hospital, there are always between 20 to 30 people waiting ahead of you.”

It took six months to get a diagnosis, and by that time, she needed surgery.

Thankfully, the 74-year-old recalls, a friend had advised her to ask about a project run by surgeons that help breast cancer patients get their surgery quicker on the public health system: Project Flamingo.

Within two weeks, Borg was scheduled for surgery. She had a double mastectomy in September, 2018.

“They saw that the [surgery] list was too long, so they formed Project Flamingo,” Borg said. “They gave up their own time on a Saturday to do these operations.”

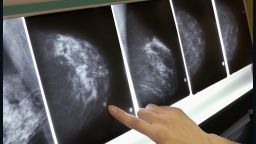

Breast cancer is often detected at a late stage, with one study finding that the time to diagnosis in Cape Town was on average 8½ months. Waiting times for a mastectomy after diagnosis can be up to four months in South Africa.

Project Flamingo, founded by surgeon Dr. Liana Roodt, aimed to fix this after Roodt routinely experienced this in her clinic at Groote Schuur, a state-funded teaching hospital in Cape Town.

Borg, who also went through cervical cancer when she was 31, now volunteers at the charity to make sure women don’t experience the same challenges she did in getting treatment early.

An agonizing wait

For eight years, Roodt has been dedicating her free time and recruiting other surgical volunteers and nurses to get a backlog of vital life-saving surgery scheduled – for free.

“So many operations need to be done quickly,” Roodt said. “But people were waiting three or four months after diagnosis before they could actually get their surgery done.”

Many operating rooms across the country were empty on weekends and public holidays, so in 2010, Roodt started raising funds to schedule and pay for the necessary facilities and nurses on those days.

“I just wrote an email to everybody in my email inbox,” she recalled, confessing that she didn’t know how to proceed at the beginning.

A few survivors of breast cancer responded right away, and some of her colleagues offered to help kick-start her vision by volunteering their own free time to perform surgeries. Roodt admitted that it took “quite a few years to gain momentum.”

500 free surgeries

Getting the right permissions and regulations in place took an astonishing three years, Roodt said.

Even so, more than 500 women have benefited from mastectomies after Roodt and other surgeons began devoting their time freely.

Her “catchup” surgeries reduced the backlog at Groote Schuur from a 12-week wait to between two and four weeks.

The project has spread to nearby Tygerberg hospital, another public health institute in Parow, Cape Town, where Borg had her surgery.

Thanks to Roodt’s determination, Project Flamingo has managed to recruit about 10 regular surgical professionals, 10 anesthetists and 10 volunteers who make up 15 staff members devoting their time to each hospital.

“We’ve had enough people willing to donate their time. … Finding nursing time is a challenge, so we pay nursing staff,” Roodt said.

To make the process fair, Roodt and her team do not select the patients to benefit; instead, they’re chosen from those already on the hospitals’ systems.

“At least six to 15 surgeries are performed a month,” Roodt said. “Some of the patients have paid a small fee depending on their income. This is in agreement with the billing policy of the Department of Health to cover their hospital admission. We take care of the expensive part: the surgery.”

Lack of options

A recent report from a group of surgeons in South Africa suggested that the number of specialist breast centers nationwide needs to be increased to cope with demand.

“The standard we are saying is that you should not wait more than 30 days between going to see a doctor and getting a [breast cancer] diagnosis and we think that is possible,” said Dr. Sarah Rayne, a surgeon and co-author of the 2017 report.

“Even in Johannesburg, where you have one of the best centers with the best outcomes, they fail to reach that target more than 60% of the time.”

Rayne says the problem goes beyond timely operations.

“More than 87% of our [South African] patients require chemotherapy. It means that by operating alone you won’t cure that person of cancer. Chemotherapy is only available in five or six centers in the whole country,” Rayne said.

Radiation equipment is also scarce. “I think in the whole of Africa, more than half of them [radiotherapy machines] are in South Africa,” Rayne said.

There are more machines in the US than the whole of Africa based on the data collected by the International Atomic Energy Agency.

The other challenge is the health system itself.

“In South Africa, more than 65% of the population exist on less than 1,000 rand ($72) a month,” Rayne said.

“Only 13% have private health care. Meanwhile, 70% of the doctors in South Africa only work in the private health system.”

The problem is amplified in rural areas. “The health clinic may not be staffed very well because the specialists don’t live in that area.”

“Doctors have left the provincial hospitals because there’s persistent prolonged shortages of staff caused by austerity measures put in place by the provincial government,” Mvuyisi Mzukwa, a chairman for the KwaZulu-Natal coastal branch of the South African Medical Association, told CNN in an earlier interview.

But this is not a problem that’s unique to South Africa. It’s echoed across the continent.

Doctors going overseas

South Africa has about six surgeons per 100,000 people. The ratio in the United States is 36.

Nigeria, despite having overtaken South Africa as the continent’s largest economy, has just one trained surgeon per 100,000 people.

A 2018 report by NOIPolls, a local polling company and advocacy group Nigeria Health Watch, noted that there were 72,000 nationally registered Nigerian doctors, according to the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria, but only 35,000 practice in the country.

Many doctors have emigrated to practice in the UK and US, the report notes.

In Ghana, Dr. Verna Vanderpuye, a consultant clinical oncologist at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, says it is hard to find the competency. “The quality of cancer surgeries is also very important,” she said, suggesting that surgical skills are limited in rural areas.

Both Rayne and Vanderpuye admit that persuading patients to have a mastectomy is also difficult.

“For young women, there’s the fact that when they have a mastectomy, they only have one breast, and some, they lose their spouses and their position in the society,” Vanderpuye said.

In a 2018 study, she found that a fear of mastectomy was the primary reason Ghanaian women present with advance stages of the disease.

Fear of treatment was also among the reasons why some women in South Africa had advanced breast cancer.

Feeling like a woman

“In an ideal setting, psychological support, counseling and even practical things like bereavement counseling are super important but seen as a luxury right now,” Roodt said.

In South Africa, Project Flamingo started distributing pampering packs to patients that included bathroom essentials, magazines and beauty treats, all for free.

So far, 4,500 packs have been given away by Roodt and her colleagues and friends.

“We were trying to show that even though being in hospital can be a daunting experience and you see us running around the wards, we actually do care. … This diagnosis does not mean you lose your feminist spirit, even though it feels like it,” Roodt said.

They can still feel like a woman despite what they are going through, she adds.

Michelle Rennie survived breast cancer 18 years ago, at the age of 46, and is now a director for Project Flamingo, sourcing products for the pamper packs.

“These pamper packs have helped to build a community,” Rennie said.

“We give them to each newly diagnosed woman,” she added.

To combat the loneliness that many cancer patients experience, the project also connects survivors like Borg and Rennie with new patients who offer mentorship and support throughout treatment.

Follow CNN Africa on social media

For Borg, this kind of relationship building is important. “Only if you have been through this can you understand what these people are doing,” Borg said. “I had a wonderful husband that went with me every day and sat with me every day, but there was a woman next to me with no one.”

Although Roodt has now joined private practice, she still devotes her unpaid time to the project, seeing patients at Groote Shuur.

She has expanded the project to cover other cancers and complications from cancer, such as colorectal cancer.

“Many [colorectal cancer patients] develop stomas and have to walk around with a poo bag attached onto their stomachs. But some of those stomas can be reversed after a period of time,” she said.

“Imagine having a poo bag attached for two to five years and dealing with a stoma when you are living in a shack with no electricity and no running water,” Roodt said. “It’s a complete nightmare. It’s not good enough to just take care of the cancer but the quality of life is terrible.”

“There is a part of me that is hopeful of there not being a need for Project Flamingo,” she said. “For a health-care system that is equal and fairer.”

That is a “pipe dream” for now, she realizes, and so the project will continue to run for as long as it is needed.

On the unexpected success of the project, Roodt added: “The amazing thing is the power of human stories. It’s people telling their stories and humanity responding to it.”

Graphics by Sarah-Grace Mankarious and Gabrielle Smith